|

It's a testament to dedication of the contractors (who don't take on more than one job at a time) and the work of their team of craftsmen and artisans that owners are still happy this far along on a job.

Lance Middlebrook is a decorative artist who spent days at the house, formulating colors to match what we found beneath years of wallpaper. His shade for the hallway we dubbed "Holleywood Green". It's a glaze that must be carefully layered and results in a breathtaking depth to the walls, showing traces of texture. Rob is making good progress on cabinets of Douglas fir he milled on site. Tile splash in the kitchen doesn't cut off where the stove will be, it extends all the way down to the floor. Tiles aren't repro, they are original subway tiles, another gem acquired from Demolition Depot. Vintage subway tiles have a special gleam from a glaze that can't be achieved today. Why? It's illegal. Original glaze was made using arsenic. Bon appetit!

Rob and Bill and Matt do all of the carpentry on site. The garage has been commandeered as a workshop. When winter came, they built a little porch off the garage, so they could work under cover in the cold.

In 1860, the spiral staircase was moved from the front of the house to the back. Which created a gap that was left unprotected for generations. It's a wonder the youngest residents survived such a hazard. Rob and Ellen closed off the gap with a handsome ballustrade created from complementary railing posts they donated to the project, acquired on a long-ago trip to New Orleans. Matt, a master carpenter on the job, took pains to match quarter sawn cherry handrail to the shape of the existing banister. Mike Zordan and his brother are plasterers who learned the trade from their father and grandfather. They've plastered many fine homes in the area, and as far away as Boston. They're giving Holleywood a facelift from top to bottom.

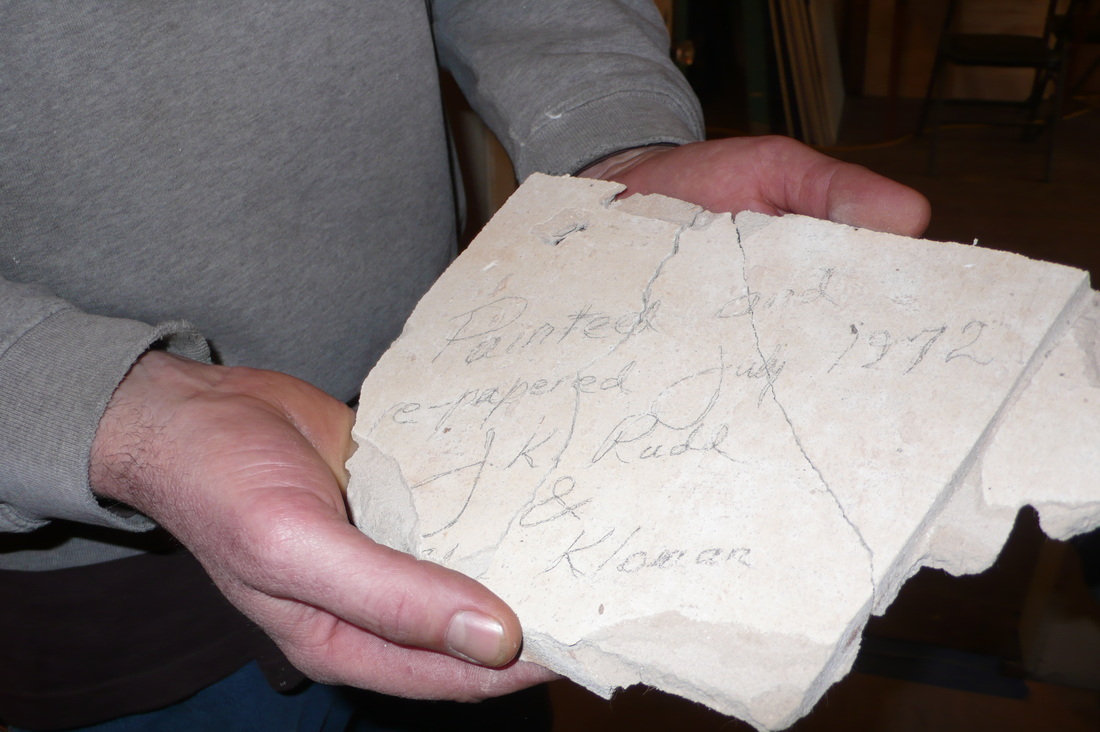

After marking out reference points, Bill cuts thru plaster, removes wood laths, launches into two layers of brick. Ah, renovation. People who have been through it know you can't change one thing without altering another. Like, putting in a bathroom on the third floor. We discover this requires adding a new window. Three challenges: 1. Approval by Historic District Board (check) 2. getting through two courses (layers) of brick, and 3. centering the window (for aesthetics) inside the wood trim that wraps around the house, so when you see the window from outside, it'll appear to have been there since 1853.  On the third floor, in a room where a cistern used to be, there's a wall that used to be an exterior. A cross section of the wall tells us what the original house was like: 2 layers of stucco, chestnut post and beam "that was deadly accurate, totally plumb," Rob says. "The masons who built this house were dead on." The color of the stucco is darker than the stucco on the house's exterior now, no doubt because it's taken a century less weatherbeating. |

who we areWe are a couple of Upper West Siders from NYC who never set out to buy an old mansion in Connecticut. But the moment we walked through its massive front door, we were smitten. The info on this site is earnestly cobbled from a variety of sources, including the web. Please let us know if we've gotten something wrong, or if there's a story about Holleywood you'd like to share. forewords

December 2021

glossary

All

|

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed