from The Lakeville Journal, April 21, 1977

We are grateful to The Lakeville Journal for chronicling the house and to resident of Holleywood's gatehouse, Troy Tatsapaugh, for preserving the issue in which John K. Rudd and his wife Jinny were interviewed in 1972. They were the parents of John Holley Rudd, the seller of the house, who has lived in the Midwest for many years. Troy's grandmother lived in the gatehouse from 1943 to 1993.

Excerpts from 1977 article by Katharine Dunn,

photos by Mary Lou Estabrook

The earliest American Holleys settled in Lakeville in 1776. Alexander Hamilton Holley was born in 1804 and named after the Federalist whose politics his parents admired.

By 1820, when Alexander was ready for college, his father was senior partner of a prosperous mining firm, Holley and Coffing. Chronic headaches militated against academic work so the boy entered the firm. Twenty four years later, he founded a company to make pocket knives from the local ore and, in 1844, built his factory on the Journal's present site.

By 1850, Alexander Hamilton Holley was the twice widowed father of 2 sons and a daughter. Successful businessman and devotee of Lakeville, he now had time and impulse to turn house designer. As his diary tells us, he drew 30 to 40 plans before completing his final drawings.

photos by Mary Lou Estabrook

The earliest American Holleys settled in Lakeville in 1776. Alexander Hamilton Holley was born in 1804 and named after the Federalist whose politics his parents admired.

By 1820, when Alexander was ready for college, his father was senior partner of a prosperous mining firm, Holley and Coffing. Chronic headaches militated against academic work so the boy entered the firm. Twenty four years later, he founded a company to make pocket knives from the local ore and, in 1844, built his factory on the Journal's present site.

By 1850, Alexander Hamilton Holley was the twice widowed father of 2 sons and a daughter. Successful businessman and devotee of Lakeville, he now had time and impulse to turn house designer. As his diary tells us, he drew 30 to 40 plans before completing his final drawings.

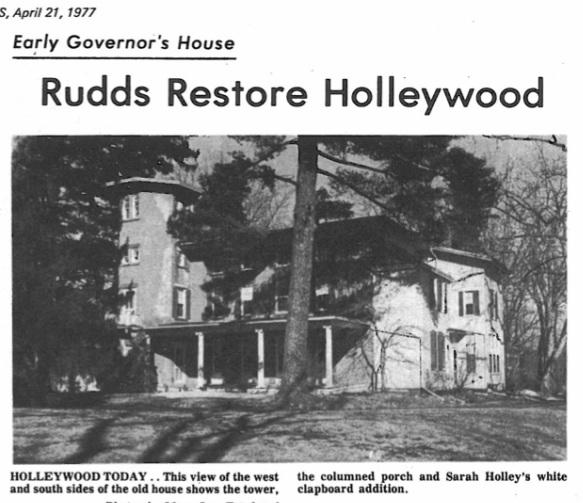

In September 1850, the distinctive gravel and mortar plastering over the exterior bricks was begun. Ohio paint mixed with this plaster gave the walls their enduring rough brown finish. Sturdy, four-square like a small Renaissance palace, the 3-storied house has outer walls 14 inches thick. It's special and endearing feature is the 4-story octagonal tower attached to the northwest corner at the right of the front door. And 1894 photograph shows the tower romantically ivy-covered. The ivy died during the hard winter of 1918.

The roof of the one-story porch running along the west wall is still supported by the same white solid walnut (not, as was more usual, hollow) Ionic columns which had been handcarved in 1798 or 1799 for the white Salisbury Church. This church was being remodeled in 1850. Holley writes in his June Diary, "Brought home 4 of the Meeting House columns bought of Richardson."

The roof of the one-story porch running along the west wall is still supported by the same white solid walnut (not, as was more usual, hollow) Ionic columns which had been handcarved in 1798 or 1799 for the white Salisbury Church. This church was being remodeled in 1850. Holley writes in his June Diary, "Brought home 4 of the Meeting House columns bought of Richardson."

In 1857 Alexander Holley, a Whig, became Governor of Connecticut. It was a one year term then and that was all he served. However, Sarah Coit Day, who had become his third wife the year before, foresaw a long public life. The 3 small rooms on heach side of the center hall seemed unsuitable for the large receptions required by her husband's position. So in 1860 the partitions were removed.

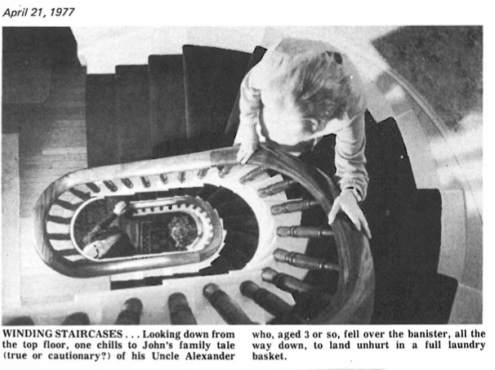

Just left of the double entrance doors, in what is now part of the dining room, a beautiful spiral staircase wound up to the 3rd floor. Undismayed by the formidable problems, she had the entire structure moved to the back of the hall. Her plan worked and is an aesthetic improvement over that of her husband.

From the end of the center hall rises the coiling staircase with its satiny uncarved rounded mahogany banister. A curved wall, like a secton of a cylinder, supports the structure, leaving space between it and the windowed back wall of the house.

Just left of the double entrance doors, in what is now part of the dining room, a beautiful spiral staircase wound up to the 3rd floor. Undismayed by the formidable problems, she had the entire structure moved to the back of the hall. Her plan worked and is an aesthetic improvement over that of her husband.

From the end of the center hall rises the coiling staircase with its satiny uncarved rounded mahogany banister. A curved wall, like a secton of a cylinder, supports the structure, leaving space between it and the windowed back wall of the house.

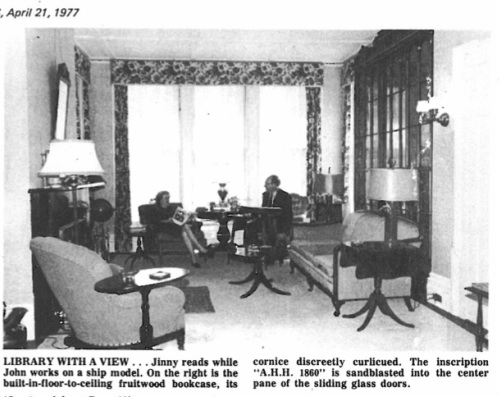

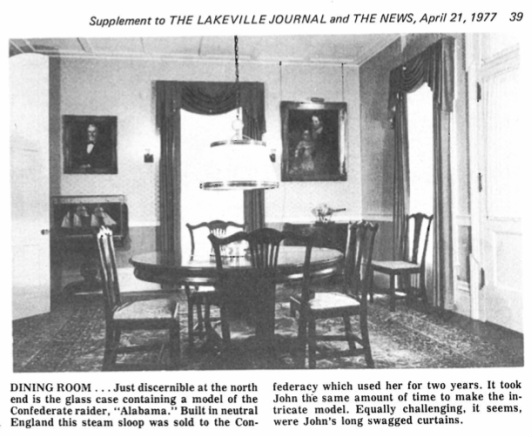

Back of the dining room is the library, which has the only working fireplace in the house. The mantel is black tan-veined Carrara. The small den to the west of the library is an efficient contemporary room with red eagle-pattern paper on one wall (peeling, but still there) and such a lovely view of the lake that little further decoration is needed.

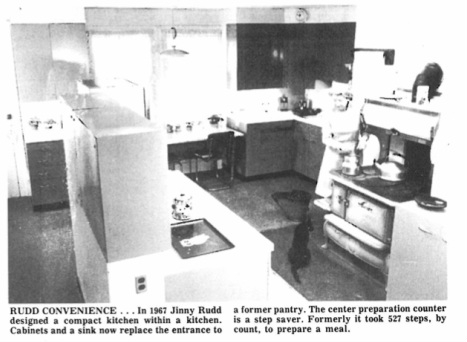

The pantry, kitchen and laundry are a cheerful workable concession to today's busy living. The St. Charles kitchen steel cabinets and formica countertops are a soft bittersweet shade. Two large rectangles of indirect light were installed by John in the kitchen ceiling. The coal stove was put in by Mrs. Charles Rudd. The second stove is a 1967 gas model.

In 1860 the 2-story white clapboard extension was built, enlarging the lakeside rooms. John says that after his great-grandfather's completion of the house in 1853 there are 2 important dates in its history: 1860, the year of Sarah Day Holley's alterations, and 1915, when his father inherited it. Charles E. Rudd installed electricity, added bathrooms and replaced the original front doors with a single door. The old doors are neatly stored, along with countless other treasures, in the basement. (Alas, no doors remain in the basement. We assume they were purchased by lucky shoppers in the tag sale.) UPDATE: We found the doors! Intact with original hardware! They were in the basement after all. Right next to a gravestone.

The pantry, kitchen and laundry are a cheerful workable concession to today's busy living. The St. Charles kitchen steel cabinets and formica countertops are a soft bittersweet shade. Two large rectangles of indirect light were installed by John in the kitchen ceiling. The coal stove was put in by Mrs. Charles Rudd. The second stove is a 1967 gas model.

In 1860 the 2-story white clapboard extension was built, enlarging the lakeside rooms. John says that after his great-grandfather's completion of the house in 1853 there are 2 important dates in its history: 1860, the year of Sarah Day Holley's alterations, and 1915, when his father inherited it. Charles E. Rudd installed electricity, added bathrooms and replaced the original front doors with a single door. The old doors are neatly stored, along with countless other treasures, in the basement. (Alas, no doors remain in the basement. We assume they were purchased by lucky shoppers in the tag sale.) UPDATE: We found the doors! Intact with original hardware! They were in the basement after all. Right next to a gravestone.

A 100-foot tulip tree dominates the foreground view from the southwest bedroom. The lake stretches beyond. The large master bedroom, which is over the dining room, has a splendid wall of closets, one with louvred doors, all constructed by John. Its only link to the past is the evidence of the old stairwell and room partition shown by faint ridges on the ceiling, reminder of the old pre-alteration plan.

The only parts of the house completely unchanged since the 1850s are the basement, the fourth floor tower room and the entire third floor. Sarah Holley's displaced staircase ends at this empty, unpainted third floor. It was here that the children of Charles E. Rudd's generation slept. At the north end of the top floor is the curved wall of the old stairwell, all that survives of the original staircase plan.

A tiny steep stairway with steps hardly 6 inches deep leads from the 3rd floor tower room to the empty room at the tower's top. Here 8 rounded-topped windows look down and far out over the lake. Seen through rectangles of blue, yellow, red, green, purple-pink and white glass, most of it the original panes, the view is almost unbearably romantic.

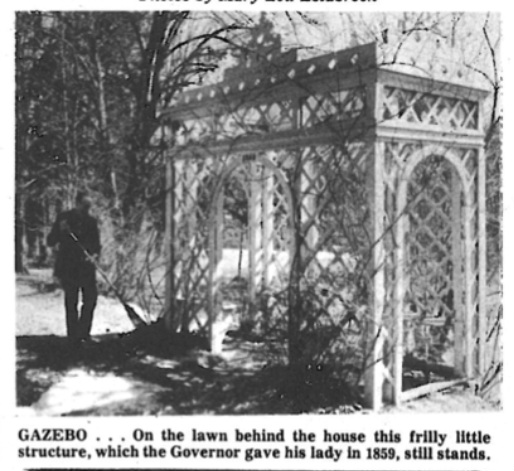

NOTE: Unfortunately, the Gazebo was sold in the Tag Sale. If you know of its whereabouts, please tell its present owners that we are interested in returning it to its origins on the premise.

The only parts of the house completely unchanged since the 1850s are the basement, the fourth floor tower room and the entire third floor. Sarah Holley's displaced staircase ends at this empty, unpainted third floor. It was here that the children of Charles E. Rudd's generation slept. At the north end of the top floor is the curved wall of the old stairwell, all that survives of the original staircase plan.

A tiny steep stairway with steps hardly 6 inches deep leads from the 3rd floor tower room to the empty room at the tower's top. Here 8 rounded-topped windows look down and far out over the lake. Seen through rectangles of blue, yellow, red, green, purple-pink and white glass, most of it the original panes, the view is almost unbearably romantic.

NOTE: Unfortunately, the Gazebo was sold in the Tag Sale. If you know of its whereabouts, please tell its present owners that we are interested in returning it to its origins on the premise.